Fair warning: As the hero in my first novel is an architect, the next several blog posts will be focusing on architects and architecture during the late Georgian Era and Regency. You may end up knowing way more about what type of paper architects used for drafting in the early 1800s.

Today’s subject, however, is not paper. It’s the Royal Academy of Arts!

The Royal Academy of Arts (“RA”), which is best known for its annual summer exhibitions, was founded in 1768. The exhibitions are known for their displays from sculptors, painters, and architects. Its story begins when Sir William Chambers, an English architect who had once tutored the king, brought a petition signed by 36 artists and architects to King George III to establish a society for promoting “Arts of Design.” They also proposed a School of Design and an annual exhibition. The king signed the instrument of foundation on December 10, 1768.

Part of the allure for King George was the minimal expense the RA would incur the Crown–no expense. The RA was free for students and was financed by the annual exhibitions–the initial admissions fee was one shilling. Although the king took a keen interest in the finances of the RA, the institution proved self-sufficient, except for possibly in the first few years. In 1775, Sir William Chambers won the commission to design the new Somerset House, located on the Strand, which would be the home of the Royal Academy until the 1830s.

There were four chairs elected in 1768 from the 36 original Academicians. The schools were: painting, architecture, perspective and geometry, and anatomy. The first architecture chair, aka “Professor of Architecture,” was Thomas Sandby. The duties of the originally appointed professors were to give six lectures annually. Those lessons in architecture were to be “calculated to form the taste of the students, to instruct them in the laws and principals of composition, to point out to them the beauties or faults of celebrated productions, to fit them for an unprejudiced study of books, and for a critical examination of structures.” By the time of the Regency, the only real restriction on the lectures was that no one was to criticize the work of a living architect. All lectures were open to male non-professionals as well as professionals.

While art students were subject to academic drawing exercises, architecture student could present their hours in an office in lieu of those in the studios. Architecture students spent their time in the library and attending lectures. The Library was stocked with leading European and British treatises and architectural publications. The curriculum was designed to complement what was learned by students in the office of a competent architect. The RA Schools offered the architectural students an annual course of six lectures from the Professor of Architecture (though on the first professor, Thomas Sandby, proved particularly reliable). They could also attend lectures given by the Professor of Perspective to try to glean some technical knowledge in that subject.

Most importantly, the students could compete for the RA prizes of one or more silver medals for a pen-and-wash drawing of a building within a ten-mile radius of London and a Gold Medal for the best composition in architecture, which required a plan, elevation and a section. (For a wonderful explanation of the different types of architectural drawing, please see the Soane Museum’s article.) The Silver Medal was given annually and was the first marker of a recently enrolled student’s progress; the biennial Gold Medal marked graduation for the most able. All Gold Medal winners, whether painters or architects, then competed for a 3-year travelling scholarship, which consisted of a royal pension of £60 per annum plus £30 travelling expenses each way. The travelling studentship was the most desirable prize of all. Once on the continent, the students were expected to send home drawings for a theoretical project for the annual exhibition

Sending students abroad was discontinued from 1795 until 1818 due to the wars with Napoleon. During the wars, architects still managed to travel but had to be rather inventive. Robert Smirke (future architect of the British Museum, the Royal Mint, and Covent Garden Theatre), from 1801 until 1805, took a Grand Tour in which he visited Brussels, Paris (in order to visit he had to disguise himself as an American), Berlin, Potsdam, Prague, Dresden, Vienna, and multiple cities in Italy and Greece. Charles Robert Cockerell (not a student of the academy, but became Professor of Architecture there in 1840), avoided France and Italy, and from 1810 to 1817 chose to go to Constantinople and Greece. Greece was a particularly popular spot for study during the Napoleonic wars, and perhaps suggests one reason why the influence of classical architecture was so strongly felt during the Regency Era.

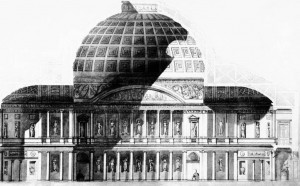

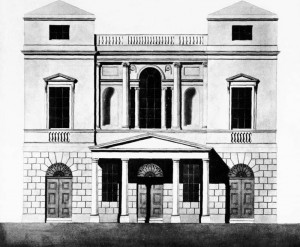

Aside from the awards, the annual exhibition could be particularly valuable as patrons sometimes selected an architect’s work on the basis of their projects displayed. James Wyatt, for instance, displayed his drawings for the Pantheon on Oxford Street, and many private commissions followed, cementing his career at a relatively young age. No wonder, given the amazing detail of his designs!

- Floor Plan of John Wyatt’s Pantheon, circa 1769

- Cross Section of Wyatt’s Pantheon

- Elevation of Wyatt’s Pantheon

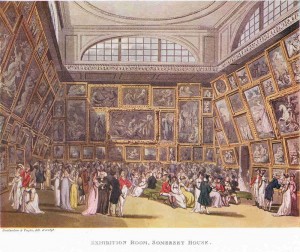

136 works of art and architecture were shown at the first exhibition in 1769, and the numbers increased dramatically. In 1819, for instance, there were 1248 exhibits. Literary critic Joseph Baretti described the Exhibition Room as “undoubtedly at the date, the finest gallery for displaying pictures so far built.” It would need to be to hold so many works of art!

Exhibitions were accompanied by an Annual Dinner, which was restricted in 1809 to 120 invites, exclusive of the members of the RA. The invitations were limited to “persons in elevated situations, of high rank, distinguished talent, or known patrons of the art” and each person was balloted by members of the Council and could be blackballed if two persons chose to do so. For the Royal Academicians, this dinner was a great opportunity to make new connections and find potential avenues of future patronage.

Given the unreliability of the lectures from the professors, the real benefit to students during the Regency era was access to the library at Somerset House and the ability to participate in the exhibitions to compete for prizes. For established architects, being an Academician was not a necessity for a successful career. It was extremely difficult to attain such a position given the limited spots that were available and the politics it took to gain the position. Between 1792 and 1820, when Benjamin West was president of the RA, only forty Academicians and 15 Associates (who were the candidates for future vacancies in the RA) were elected. Of those, only two Academicians were architects: Robert Smirke and John Soane. Joseph Gandy was the only Associate in architecture added during West’s tenure. (Keep in mind that many, many more architects would have participated in the annual exhibitions–it wasn’t a requirement to be an Academician to display art in the exhibitions). This leaves many prominent architects of the era out in the cold. One finds very little evidence of John Nash, for instance, the premier architect of the Regency Era, having much to do with the RA, yet his biggest competition, John Soane, centered much of his professional life around the institution. The RA was only one avenue to success.

Speaking of Soane, it would be impossible to discuss the Royal Academy during the Regency Era without discussion of the architect of the Bank of England. Soane (1753-1837), the son of a bricklayer, rose to the top of his profession and became the Professor of Architecture for the RA and an Official Architect of the Office of Works. Soane trained under George Dance the Younger who was a founding member of the RA. He then trained under Henry Holland and was a student of the Royal Academy as well. He was awarded the Academy’s silver medal in 1772 for a measured drawing of the facade of the Banqueting House, Whitehall, and then the gold medal in 1776 for his design of a Triumphal Bridge. He received a travelling scholarship in December 1777 and embarked on his Grand Tour the following year. When he returned in 1780, despite the pension, he was £120 in debt. Soane began finding professional success in the mid-1780’s, and October of 1788, he succeeded Sir Robert Taylor as architect and surveyor to the Bank of England. This job, and particularly the connections and contacts that came with it, elevated Soane’s career.

Soane centered his career around the RA. Between 1772 and 1836, there were only five years that Soane did not exhibit any designs at the RA. In November 1795, Soane was elected an Associate Royal Academician and in February 1802, Soane was elected a full Royal Academician.

Soane hoped to replace George Dance as Professor of Architecture as Dance had failed to deliver a single lecture since his appointment in 1798. But in December of 1804, Dance received an anonymous letter that Soane was plotting to replace him. It ended their friendship. However, Dance eventually stepped down, and in 1806, Soane became Professor of Architecture.

Following his election in 1806, Soane set about preparing his lectures to be given each year. In order to elucidate his theoretical points, Soane commissioned over 1,000 watercolor drawings, a costly and labor-intensive exercise, which suggests Soane dedication to the RA. These drawings, rendered by pupils from Soane’s own architectural firm, were to many the most appealing part of the lectures. Soane’s high-pitched delivery was incomprehensible, though better than his other colleagues in the Academy. The drawings were in three main divisions: first, those based on engravings from architectural folios from Soane’s own library; then, those drawn by pupils on many site visits in London; finally, a large number were based on Soane’s designs and on drawings by earlier architects in his collection. Soane illustrated work by almost every major architect of his day, especially in London. However, he included nothing whatsoever by his rival, John Nash, a result of envy but also of his low opinion of Nash’s craft.

The lectures were interrupted in 1810 by academicians disagreeing with Soane’s criticism of a living architect’s work – Robert Smirke’s Covent Garden Theatre in Drury Lane. While the building had received widespread praise upon its opening, Soane called it an example of “sacrificing everything to one front of a building”. Listeners of this lecture hissed as he spoke while others clapped. Smirke was not the only one to receive this criticism in these lectures. Soane also had harsh words for Robert Adam’s Lansdowne House and Leoni’s Uxbridge House as further examples. Royal Academicians Robert Smirke (painter), father of the architect, and his friend Joseph Farington campaigned against Soane, and consequently the RA introduced a rule forbidding criticism of a living British artist in any lectures. Soane, only under the threat of termination, amended his lectures.

Soane’s twelve lectures covered a wide-array of topics. They covered everything from the history of architecture to correct use of decoration and from the design of doors and windows to construction methods. He praised St. Paul’s Church, Coven Garden, by Inijo Jones, and Sir John Vanbrugh’s compositions t Blenheim and Kingson Weston. He opposed the destruction of 16th and 17th-century historic mansions, as well as the alteration of those which survived. Additions should be appropriate–adding a classical structure to an existing Gothic building was in poor taste according to Soane.

Soane was Professor of Architecture until 1837. Upon his death, William Wilkins succeeded him. Wilkins gave no lectures himself before he died in 1839.

Sources:

Online:

Royal Academy of Arts

“Perspectives from Sir John’s Podium,” 13 January 1997, http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/books/perspectives-from-sir-johns-podium/160485.article

Print:

Graves, Algernon, The Royal Academy of Arts; a complete dictionary of contributors and their works from its foundation in 1769 to 1904, London, H. Graves and co., ltd.: 1905-06.

J. E. Hodgson and Fred. A. Eaton, The Royal academy and its members 1768-1830, Charles Scribner’s Sons, London: 1905.

Darley, Gillian, John Soane An Accidental Romantic, Yale University Press: 1999.